Antibody Treatment Could Block Gut-Derived Toxin Behind Kidney Fibrosis

A gut microbe molecule drives diabetic kidney scarring. Blocking it may offer new treatment options.

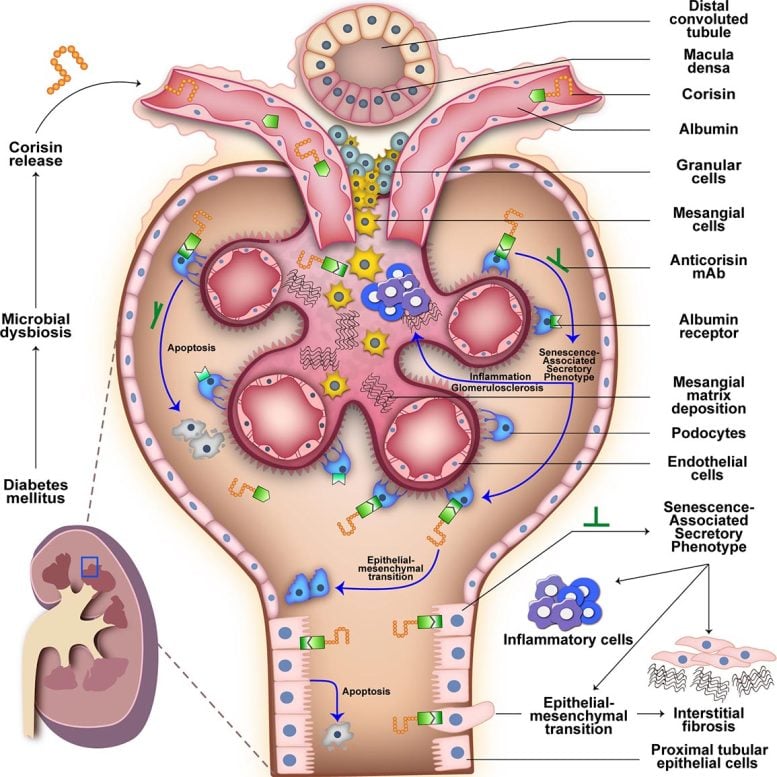

A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and Mie University in Japan has revealed that a molecule produced by gut bacteria can travel to the kidneys, where it triggers inflammation, tissue scarring, and fibrosis. These processes represent a serious complication of diabetes and are among the leading causes of kidney failure.

The molecule, known as corisin, is a small peptide generated by Staphylococcus bacteria in the gut. Researchers detected elevated levels of corisin in the blood of patients with diabetic kidney fibrosis. To understand its role, they combined computer simulations with tissue and mouse experiments, tracing how corisin moves from the gut to the kidneys, how it drives kidney damage, and how antibody-based treatments might help block its harmful effects.

“Our earlier studies showed corisin can damage cells and worsen tissue scarring and fibrosis in other organs, so we suspected it might be a hidden driver of kidney fibrosis,” said Illinois animal sciences professor Isaac Cann, who led the study with Mie University immunology professor Dr. Esteban Gabazza. Cann and Gabazza are affiliates of the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at Illinois. “Our new findings suggest corisin is indeed a hidden culprit behind progressive kidney damage in diabetes, and that blocking it could offer a new way to protect kidney health in patients.”

The researchers published their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

A hidden driver of diabetic kidney damage

Dr. Taro Yasuma of Mie University, a physician and first author of the study, explained that diabetic kidney fibrosis is one of the leading causes of kidney failure worldwide. Despite its impact, the main factors driving the condition have remained unclear, and no therapies currently exist that can halt its progression.

“Many people with longstanding diabetes eventually develop kidney fibrosis, and once it progresses, there are limited options beyond dialysis or kidney transplantation. Current treatments mainly focus on controlling blood sugar and blood pressure, but there’s no cure that stops or reverses the scarring or fibrotic process,” Yasuma said.

To investigate further, the team analyzed blood and urine samples from patients with diabetic kidney disease. Their results showed that these patients had much higher levels of corisin compared with healthy individuals, and that the concentration of corisin in the blood was directly linked to the severity of kidney damage.

Tracking corisin from gut to kidney

Upon seeing the same results in mice with kidney fibrosis, the researchers tracked what corisin was doing in the kidneys of the mice. They found that corisin speeds up aging in kidney cells, setting off a chain reaction from inflammation to cell death to a buildup of scar tissue, eventually resulting in the loss of kidney function and worsening fibrosis.

But how was corisin getting from the gut to the kidneys? Cann and Gabazza’s groups collaborated with U. of I. chemical and biomolecular engineering professor Diwakar Shukla’s group to produce computer simulations and laboratory experiments to follow corisin’s journey from the gut to the bloodstream. They found that corisin can attach to albumin, one of the most common proteins in blood, and ride it through the bloodstream. When it reaches the kidneys, corisin detaches from the albumin to attack the delicate structures that filter blood and urine.

Antibody treatment shows promise

To confirm that corisin was the main culprit behind the kidney damage, the researchers gave the mice antibodies against corisin. They saw a dramatic reduction in the speed of kidney damage.

“When we treated the mice with an antibody that neutralizes corisin, it slowed the aging of kidney cells and greatly reduced kidney scarring,” said Gabazza, who also is an adjunct professor of animal sciences at Illinois. “While no such antibody is currently approved for use in humans, our findings suggest it could be developed into a new treatment.”

Next, the researchers plan to test anticorisin treatments in more advanced animal models, such as pigs, to explore how they could be adapted for safe use in humans. The U. of I. and Mie University have a joint invention disclosure on corisin antibodies.

“Our work suggests that blocking corisin, either with antibodies or other targeted therapies, could slow down or prevent kidney scarring in diabetes and thus enhance the quality of life for patients,” Cann said.

Reference: “Microbiota-derived corisin accelerates kidney fibrosis by promoting cellular aging” by Taro Yasuma, Hajime Fujimoto, Corina N. D’Alessandro-Gabazza, Masaaki Toda, Mei Uemura, Kota Nishihama, Atsuro Takeshita, Valeria Fridman D’Alessandro, Tomohito Okano, Yuko Okano, Atsushi Tomaru, Tomoko Anoh, Chisa Inoue, Manal A. B. Alhawsawi, Ahmed M. Abdel-Hamid, Kyle Leistikow, Michael R. King, Ryoichi Ono, Tetsuya Nosaka, Hidetoshi Yamazaki, Christopher J. Fields, Roderick I. Mackie, Xuenan Mi, Diwakar Shukla, Justine Arrington, Yutaka Yano, Osamu Hataji, Tetsu Kobayashi, Isaac Cann and Esteban C. Gabazza, 25 August 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61847-2

This study was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Takeda Science Foundation, the Japan Association for Diabetes Education and Care, the Eli Lilly Japan Innovation Research Grant, the Daiwa Security Foundation and the Charles and Margaret Levin Family Foundation.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Source link